Understanding ≠ predicting

Chaotic systems and putting your mouth where your money is –or viceversa

There has been a recent trend of enthusiasm around (super)forecasting and the like. The idea is to aggregate a bunch of guesstimates by different people –who may have access to complementary bits of information on different aspects of the same problem- obtaining a better result than individual predictions. The aggregation bit can be carried out through prediction markets or sophisticated weighting schemes. Apparently, if the latter are sophisticated enough, this technology could even be used to tackle the problem of causal inference, which plagues the social sciences.

A byproduct of the empirical success of these attempts is that a new emphasis has been placed on the ability to predict future events as a way to prove that one’s understanding is real. In other words, if you believe you have a key for understanding the unfolding of international relations, pandemics, sports -or anything really- then you better put your money where your mouth is, and make precise predictions. If you lose, then your theory was likely nonsense to begin with. For those who have read the black swan –or was it in the sequel?- science is about how not to be a sucker.

Maybe I am a sucker1 myself but –eh- I partly disagree on this one. It is possible to make kimchi out of pretty much any vegetable –I have tried green onions, cabbage obviously, radish, perilla leaf, cucumbers- so if we extend the concept a little bit, this whole line of thinking is kinda sorta what you would get if you fermented the Logik der Forschung by Karl Popper in an earthen jar. Spicy, crunchy, but still an acquired taste2. The mirror image of this, is people wondering whether large language models display genuine artificial understanding –in some meaningful sense of the word- or are merely plagiarising humans by mining statistical associations in language, as Noam Chomsky puts it.

So are understanding and predicting one and the same thing? I will argue that this is not the case -that there can be meaningful understanding without the ability to make accurate predictions- just to walk back that claim a bit further on. But just a bit.

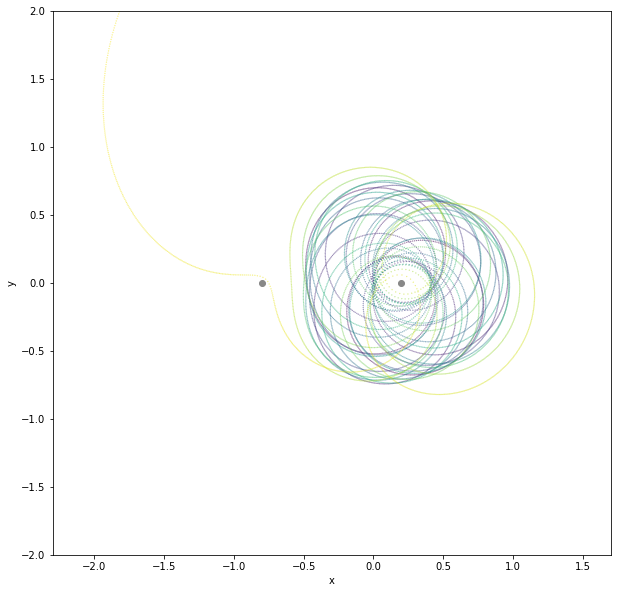

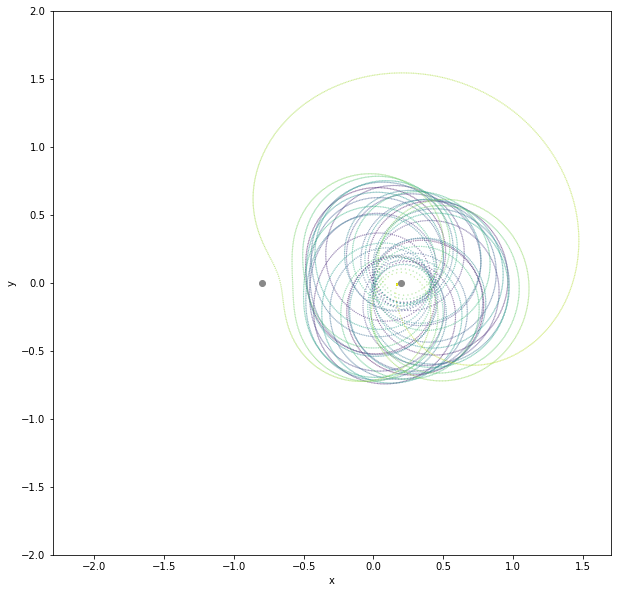

Exhibit A: the freaking three body problem. I integrated the circular restricted version of the problem starting from slightly different initial conditions, shown in the top and bottom panels of Fig. 1 below. On the first panel the initial y velocity was 2.6 and on the second 2.601 -in dimensionless units, but feel free to imagine it is km/s or something. In both cases the inhabitants of the little planet should dehydrate ASAP, but for opposite reasons: in one case their little planet is being kicked out far from their suns, and in the other case they end up falling straight into the right sun.

Now it turns out that we know this system very well. For instance we know that the Jacobi integral is constant. We know the equations of motion. We can solve them numerically –like I just did. I would go out on a limb here and say that we understand the circular restricted three-body problem. But prediction is a different business: it demands extremely accurate knowledge of the initial conditions, which we might just not have. Is our understanding of the three body problem –and ultimately classical mechanics- worthless? I don’t buy that: our understanding is incomplete, because to have a perfect knowledge of anything that can even just slightly perturb our initial conditions we would have to model too much stuff. But incomplete is a far cry from worthless.

Granted, forecasters are dealing with probabilistic predictions –probability is a way to take the holes that make our understanding incomplete, i.e. ignorance, into account- and indeed classical mechanics can be leveraged to make probabilistic predictions. Even without sophisticated theory, you can just rerun a simulation many times from slightly different initial conditions. As far as I know we are actually doing this for asteroids, resulting in an estimate of the probability of them hitting the Earth. So yes, a good theory may improve your Brier score even if you have incomplete information, as long as it is not too incomplete3.

Consider that any realistic social system is very likely to exhibit chaotic behaviour in the extreme, and you will see how supposedly worthless theories –because they cannot be leveraged to make precise predictions- might just be very incomplete, but not necessarily wrong. Marxism, psychoanalysis, realism in international relations -that kind of stuff: don’t throw them out just yet, unless you want to throw out Jacobi’s integral too.

The word for sucker is best rendered in Italian as precario della ricerca.

Personally I love kimchi. I really do.

This is the part where I walk back my statement a bit.

Hi Mario,

maybe I am misunderstanding you, and possibly I'm a bit provocative: are you saying that predictions without understanding (e.g. machine learning) is useless?

Because what you wrote sounds very much like when I told you that there is no understanding outside the world of pen and paper...

;-)

Leo

Perhaps relevant: Von Wright, Georg Henrik. Explanation and understanding. Cornell University Press, 2004. Cited by Pearl here: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/jci-2018-2001/html